Muscle Tension Headache Muscle Contraction Headache Tension-Type Headache AND Spinal Manipulation Spinal Postural Improvement

BACKGROUND CONCEPTS

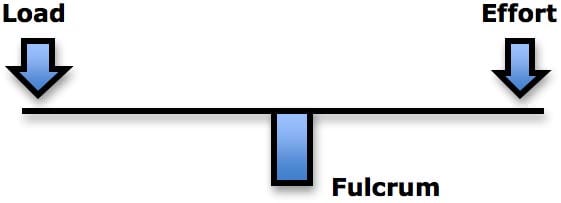

Upright posture is a first class lever mechanical system, such as a teeter-totter or seesaw:

Fulcrum

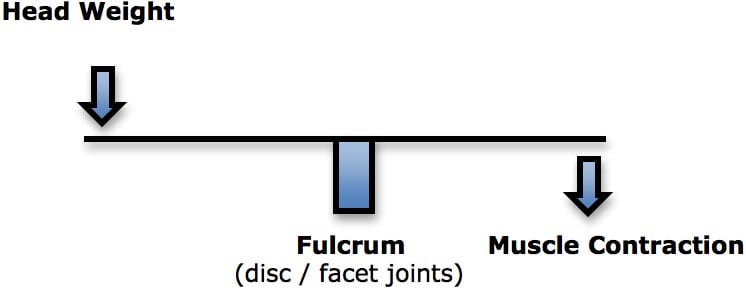

By mechanical definition, the fulcrum is where the forces are the greatest. In human spinal posture, the fulcrum is the intervertebral disc and facet joints.

When the human head is bent forward, as in looking down, the loads on the fulcrum (disc and facet joints) would be the weight of the head multiplied by the distance from the fulcrum, added by the counter-balancing contraction of the posterior spinal muscles. This counterbalance contraction of the cervical spine muscles is fatiguing to the muscle, increases the compressive loads on the fulcrum tissues, and causes a constant increased tension in the muscles. This can cause headaches.

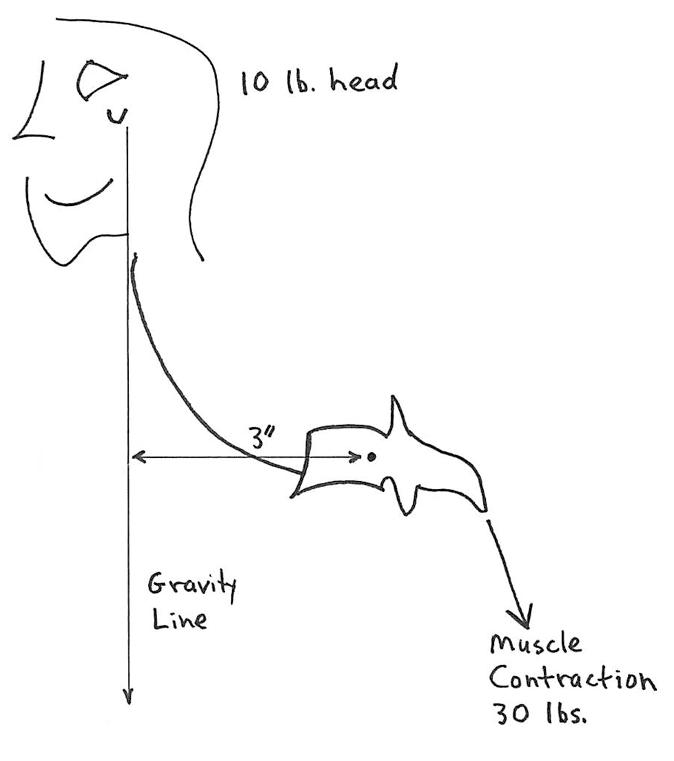

Rene Cailliet, MD, uses an example where a patient has unbalanced forward head posture (1). Dr. Cailliet assigns the head a weight of 10 lbs. and displaces the head’s center of gravity forward by 3 inches. The required counter balancing muscle contraction on the opposite side of the fulcrum (the vertebrae) would be 30 lbs. (10 lbs. X 3 inches):

Kenneth K. Hansraj, MD, is Chief of Spine Surgery at the New York Spine Surgery & Rehabilitation Medicine center. In 2014 he published an article in the journal Surgical Technology International, titled (2):

Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head

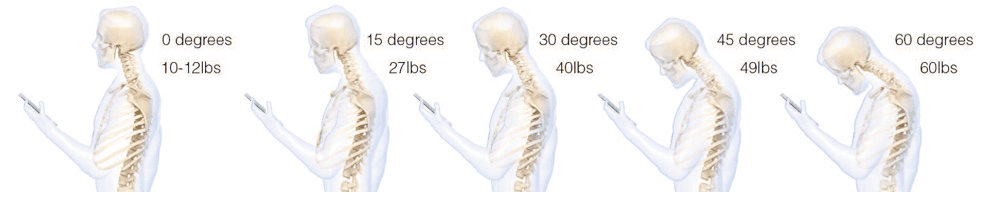

In this article, Dr. Hansraj points out that the ubiquitous use of cellular devices are creating an epidemic incidence of joint and muscular problems in the upper thoracic and lower cervical spines. He notes that billions of people are using cell phone devices on the planet, essentially in poor posture. The purpose of his study was to assess the forces incrementally seen by the cervical spine as the head is tilted forward, into a worsening posture.

Dr. Hansraj created a cervical spine model to calculate the forces experienced by the cervical spine when in incremental flexion (forward head position). His mathematical analysis used a head weight of 13.2 pounds.

Dr. Hansraj made the following observations:

“Poor

posture invariably occurs with the head in a tilted forward position

and the shoulders drooping forward in a rounded position.”

“The weight seen by the spine dramatically increases when flexing the head forward at varying degrees.”

“Loss of the natural curve of the cervical spine leads to incrementally increased stresses about the cervical spine. These stresses may lead to early wear, tear, degeneration, and possibly surgeries.”

An average person spends 2-4 hours a day with their heads tilted forward reading and texting on their smart phones / devices, amassing 700-1400 hours of excess, abnormal cervical spine stress per year. “A high school student may spend an extra 5,000 hours in poor posture” per year.

Nikolai Bogduk, from the University of Newcastle, Australia, is a Doctor of Medicine and a Doctor of Science. Dr. Bogduk pioneered research into the neuroanatomical basis for spinal pain, beginning in 1972. Through today (May 2016), he has authored numerous book chapters, books, and 254 articles located using a PubMed search of the US National Library of Medicine.

Perhaps the best article ever written pertaining to headaches was by Dr. Bogduk. It appeared in the journal Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy in 1996, and is titled (3):

Anatomy and Physiology of Headache

This article is based on an extensive review of neuroanatomy. The key concept explained by Dr. Bogduk is that all headaches synapse in the upper cervical spine (Trigeminal-Cervical Nucleus) before being relayed to the cortical homunculus for perception. This anatomical fact supports the plausibility and the anecdotal observations that people with a variety of headaches (migraine, cluster, cervicogenic, muscle tension, etc.) may obtain relief from manual therapy and/or manipulation of the upper cervical spine. Explanations for this relief tend to center around the 1965 Gate Theory of Pain (4). The Gate Theory is succinctly stated by Eric Kandel, MD, and colleagues (5):

“Pain is not simply a direct product of the activity of nociceptive afferent fibers but is regulated by activity in other myelinated afferents that are not directly concerned with the transmission of nociceptive information.”

“The idea that pain results from the balance of activity in nociceptive and non-nociceptive afferents was formulated in the 1960s and was called the gate control theory.”

The non-nociceptive afferents that close the Pain Gate are primarily mechanoreceptors (proprioceptors). When the joints and tissues of the upper cervical spine are not functioning optimally, the Pain Gate is “open,” and more pain signals arrive to the cortical brain. Spinal manipulation and other mechanical therapeutic interventions at the upper cervical spine “close” the Pain Gate (by initiating a neurological sequence of events). This will reduce the perception of any type of headache. This premise is well stated by orthopedic surgeon William H. Kirkaldy-Willis and colleague (6):

“Spinal manipulation is essentially an assisted passive motion applied to the spinal apophyseal and sacroiliac joints.”

Melzack and Wall proposed the Gate Theory of Pain in 1965, and this theory has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny.”

“The central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input.” Pain is facilitated by “lack of proprioceptive input.” This is why it is important for “early mobilization to control pain after musculoskeletal injury.”

The facet capsules are densely populated with mechanoreceptors. “Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.”

Stretching of facet joint capsules will fire capsular mechanoreceptors that reflexively “inhibit facilitated motor neuron pools” which are responsible for the muscle spasms that commonly accompany low back pain.

Restating the above, there is a potential that manual/manipulative can improve any headache as a consequence of improved proprioceptive/mechanoreceptive afferent input into the Trigeminal-Cervical Nucleus, “closing” the Pain Gate. Chiropractors and other providers of this type of manual intervention are particularly versed in Cervicogenic Headaches. Cervicogenic Headaches are referred pain to the head, where the actual primary nociceptive afferent arises in the joints and/or soft tissues of the upper cervical spine.

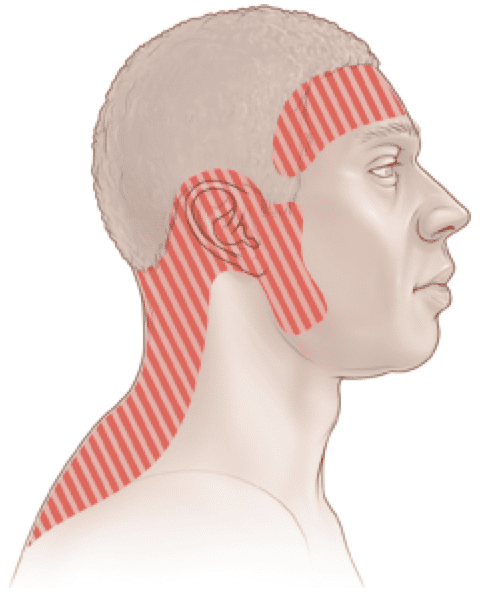

Although there may be some overlap, Cervicogenic Headaches and Tension-Type Headaches can be distinct. Tension-Type Headaches result from increased tension in the muscles of the upper back and neck, the head, and the temporomandibular joints. Hence, Tension-Type Headaches are often referred to as Muscle Tension Headaches:

••••••••••

Tension-type headache is the most common form of benign, primary headache (7). Tension-Type Headaches have been known by other names, such as Muscle Tension Headache and Muscle Contraction Headache; yet, the International Headache Society officially classified this type of headache as Tension-Type Headaches in 1988 (8).

The features of Tension-Type Headache include (9):

- The headache is bilateral

- The intensity is mild to moderate

- The pain quality is aching, tightening, or pressing

- The duration is from 30 minutes to 7 days

- The headache is not accompanied by nausea or vomiting

- Either photo- or phonophobia may be experienced, but not both

More detailed criteria for Tension-Type Headache appeared in the journal Cephalalgia in 1983, including (10):

- A minimum of at least 10 previous headache episodes meeting the criteria below:

- Headache lasting from 30 minutes to 7 days.

- At least two of the following:

- Pressing, Tightening, but Non-Pulsating quality

- Mild or Moderate intensity that may inhibit but does not prohibit activity

- Bilateral location

- Not aggravated by walking, stairs, or other similar routine physical activities

- Both of the following:

- No Nausea or Vomiting

- One of either photo- or phonophobia may be present, but not both

There are two forms of Tension-Type Headache (8):

- Episodic

The headaches are experienced no more than 180 days per year.

- Chronic

The headaches are experienced more than 180 days per year.

The prevalence of Tension-Type Headache varies between 10-65% of the population, depending upon the country and the other classification features. A review of the literature in 2003 concluded that, “slightly more than one-third of the adult population suffers from this problem (9).”

••••••••••

A number of studies have assessed the effectiveness of spinal manipulation and other manual techniques of the cervical spine for the treatment of Tension-Type Headache. Several are presented below:

A 1979 study published in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, titled (11):

Osteopathic Manipulation in the Treatment of Muscle-Contraction Headache

The

authors evaluated the benefit of a single manipulative session on nine

subjects suffering with muscle contraction headaches. The authors found

this manipulation to be helpful.

•••••

A 1995 study published in the Journal of Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics, titled (12):

Spinal Manipulation vs. Amitriptyline for the Treatment of Chronic Tension-Type Headaches: A Randomized Clinical Trial

The authors compared the effectiveness of chiropractic spinal manipulation to the drug amitriptyline for chronic tension-type headache. The study design was a randomized controlled trial with a 6-week treatment period and a 4-week post-treatment, follow-up period. The study involved 150 patients. The authors concluded:

“The spinal manipulation group showed a reduction of 32% in headache intensity, 42% in headache frequency, 30% in over- the-counter medication usage and an improvement of 16% in functional health status. By comparison, the amitriptyline therapy group showed no improvement or a slight worsening from baseline values in the same four major outcome measures.”

“The results of this study show that spinal manipulative therapy is an effective treatment for tension headaches.”

“Four weeks after the cessation of treatment, the patients who received spinal manipulative therapy experienced a sustained therapeutic benefit in all major outcomes in contrast to the patients that received amitriptyline therapy, who reverted to baseline values.”

“The sustained therapeutic benefit associated with spinal manipulation seemed to result in a decreased need for over- the-counter medication.”

It is also noteworthy that 82% of the subjects in the amitriptyline group reported side effects that included drowsiness, dry mouth and weight gain; 4% in the spinal manipulation group reported neck soreness and stiffness.

•••••

A 2005 study (from Harvard Medical School) published in the journal Headache, titled (13):

Physical Treatments for Headache: A Structured Review

The author in the study reviewed published clinical trial evidence, systematic reviews, and case series regarding the efficacy of selected physical modalities in the treatment of primary headache disorders. He noted, “Chiropractic manipulation demonstrated a trend toward benefit in the treatment of Tension-Type Headaches.”

A 2012 study (from Peninsula Medical School, Exeter, United Kingdom) published in the journal Complimentary Therapies in Medicine, titled (14):

Spinal Manipulations for Tension-Type Headaches: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the effectiveness of spinal manipulations as treatment option for tension-type headaches. Eight databases were searched and all randomized trials were considered if they investigated spinal manipulations performed by any type of healthcare professional for treating tension type headaches in human subjects. The authors concluded:

“Four randomized clinical trials suggested that spinal manipulations are more effective than drug therapy, spinal manipulation plus placebo, sham spinal manipulation plus amitriptyline or sham spinal manipulation plus placebo, usual care or no intervention.”

“The evidence that spinal manipulation alleviates tension type headaches is encouraging.”

•••••

A 2014 study (from the University of Valencia, Spain) published in the Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, titled (15):

Efficacy of Manual and Manipulative Therapy in the Perception of Pain and Cervical Motion in Patients with Tension-Type Headache: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of manipulative and manual therapy treatments with regard to pain perception and neck mobility in patients with tension-type headache. The study was a randomized clinical trial assessing 84 subjects diagnosed with tension-type headache. Four treatment sessions were administered over 4 weeks, with post-treatment assessment and follow-up at 1 month.

The intervention showed significant improvements in pain perception and ranges of motion, as well as reduced frequency of headache.

•••••

Another 2014 study (from the University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy) published in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, titled (16):

Pilot Trial of Osteopathic Manipulative Therapy for Patients with Frequent Episodic Tension-Type Headache

The purpose of this study was to explore the efficacy of spinal manipulation for pain management in frequent episodic tension-type headache. It was a single-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study, involving 44 subjects. Treatment was given over a period of 1-month, and there was a 3-month follow-up period.

The manipulation group had a significant reduction (40%) in headache frequency. The authors concluded:

“Manipulative therapy may be preferred over other treatment modalities and may benefit patients who have adverse effects to medications or who have difficulty complying with pharmacologic regimens.”

•••••

A third 2014 study (and the second study from the University of Valencia, Spain) published in the journal European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine, titled (17):

Effect of Manual Therapy Techniques on Headache Disability in Patients with Tension-Type Headache. Randomized Controlled Trial

The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of manual therapy techniques, applied to the suboccipital region, on aspects of disability in a sample of patients with tension-type headache. It was a randomized controlled trial using 67 subjects. Patients were randomly divided into four treatment groups: 1) suboccipital soft tissue inhibition; 2) occiput-atlas-axis manipulation; 3) combined treatment of both techniques; 4) control. Four sessions were applied over 4 weeks.

The authors found that headache frequency was significantly reduced with the manipulative and combined treatment. When manipulation was combined with suboccipital soft tissue techniques, there was improvement in photophobia, phonophobia and pericranial tenderness.

•••••

In 2016, a third study from the University of Valencia, Spain group, also published in the European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine, titled (18):

Do Manual Therapy Techniques Have a Positive Effect on Quality of Life in People with Tension-Type Headache? A Randomized Controlled Trial

The aim of this study was to specifically look at the effect of manual/manipulative therapy on the tension-type headache patient’s quality of life. Seventy-six subjects were treated for 4 weeks with manual therapy techniques. The authors concluded:

“Manual therapy techniques applied to the suboccipital region, for as little as four weeks, offered a positive improvement in some aspects of quality of life of patient’s suffering with Tension-Type Headaches.”

•••••

SUMMARY

Tension-Type Headache is the most common headache in society, affecting about one-third of the population. The studies presented here are often critical of the need for more and better studies, with more subjects, to thoroughly evaluate the benefit of manipulation and adjunct manual therapies for the treatment of these common headaches. However, there is clear support indicating that cervical spine manipulation and adjunct manual therapies are helpful for many suffering from these headaches. Cervical spine manipulation and adjunct manual therapies are particularly beneficial when compared to other treatment approaches, such as drugs and placebo interventions.

Additionally, long-term improvement of Tension-Type Headache may require postural improvement, especially of the Forward Head Syndrome (19). As noted above, when the head is bent forward, the posterior neck muscles must contract, resulting in “muscle contraction headache.” Chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific manipulation) is designed to both improve segmental spinal function and to also improve postural alignment. Both will benefit patients suffering from Tension-Type Headaches.

REFERENCES

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; F A Davis Company, 1996.

- Kenneth K. Hansraj K; Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head; Surgical Technology International; November 2014; Vol. 25; pp. 277-279.

- Bogduk N; Anatomy and Physiology of Headache; Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy; 1995; Vol. 49; No. 10; pp. 435-445.

- Melzack R, Wall PD; Pain mechanisms: a new theory; Science; November 19, 1965;150(3699); pp. 971-9.

- Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T; Principles of Neural Science; McGraw-Hill; 2000.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985, Vol. 31, pp. 535-540.

- Silberstein SD; Tension-type headaches; Headache; September 1994; Vol. 34; No. 8; pp. S2-7.

- International Headache Society; Classification and Diagnostic Criteria for Headache Disorders, Cranial Neuralgias and Facial Pain; Cephalalgia; 1988; Supplemental 7.

- Vernon HT; “Tension-type and cervicogenic headaches, Part 1, Clinical descriptions and methods of assessment”; In The Cranio-Cervical Syndrome; Edited by Howard Vernon; Butterworth Heinemann; 2003.

- Sjaastad O, Saunte C, Hovdahl H, Breivik H, Grønbaek E; “Cervicogenic” headache, An hypothesis; Cephalalgia; December 1983; Vol. 3; No. 4; pp. 249-256.

- Hoyt WH, Shaffer F, Bard DA, Benesler JS, Blankenhorn GD, Gray JH, Hartman WT, Hughes LC; Osteopathic manipulation in the treatment of muscle-contraction headache; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; January 1979; Vol. 78; No. 5; pp. 322-325.

- Boline PD, Kassak K, Bronfort G, Nelson C, Anderson AV; Spinal manipulation vs. amitriptyline for the treatment of chronic tension-type headaches: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics; March-April 1995;Vol. 18; No. 3; pp. 148-154.

- Biondi DM; Physical treatments for headache: a structured review; Headache; June 2005; Vol. 45; No. 6; pp. 738-746.

- Posadzki P, Ernst E; Spinal manipulations for tension-type headaches: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials; Complimentary Therapies in Medicine; August 2012; Vol. 20; No. 4; pp. 232-239.

- Espí-López GV, Gómez-Conesa A; Efficacy of manual and manipulative therapy in the perception of pain and cervical motion in patients with tension-type headache: a randomized, controlled clinical trial; Journal of Chiropractic Medicine; March 2014; Vol. 13; No. 1; pp. 4-13.

- Rolle G, Tremolizzo L, Somalvico F, Ferrarese C, Bressan LC; Pilot trial of osteopathic manipulative therapy for patients with frequent episodic tension-type headache; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; September 2014; Vol. 114; No. 9; pp. 678-685.

- Espí-López GV, Rodriquez-Blanco C. Oliva-Pascual-Vaca A, Benitez-Martinez JC, Lluch E, Falla D; Effect of manual therapy techniques on headache disability in patients with tension-type headache. Randomized controlled trial; European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine; December 2014; Vol. 50; No. 6; pp. 641-647.

- Espi-Lopez GV, RODRíGUEZ-Blanco C, Oliva-Pascual-Vaca Á, Molina-Martinez FJ, Falla D; Do manual therapy techniques have a positive effect on quality of life in people with tension-type headache? A randomized controlled trial; European Journal of Physical Rehabilitation Medicine; February 29, 2016. [Epub ahead of print]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Pareja JA; Forward head posture and neck mobility in chronic tension-type headache: a blinded, controlled study; Cephalalgia; March 2006; Vol. 26; No. 3; pp. 314-319.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”