Chiropractic and Sagittal Posture

Chiropractors are primary health care providers. This means that patients who seek chiropractic care do not need a referral from another health care provider. Patients may self-refer themselves for chiropractic assessment and treatment.

The large majority (93%) of patients who initially present themselves for chiropractic care do so for the complaints of spinal pain (1). A typical chiropractic assessment of these patients would often include:

History of the complaint; this would include information such as causative factors, duration, location, severity, factors that help or aggravate it, etc.

This type of information helps the chiropractic to determine if the condition is the type of problem that chiropractic typically helps.

Orthopedic and neurological tests; these tests are often specific for the complaint and history.

These tests help the chiropractor establish a working diagnosis as the clinical reasons for the complaints. The results can both rule-out or rule-in various pathophysiological processes.

Imaging studies, which is an optional clinical call by the chiropractor.

This would typically involve x-rays or perhaps advanced imaging such as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or even computed tomography (CT).

A chiropractic examination.

Chiropractors primarily assess and treat patients mechanically. A spinal complaint and problem that a medical doctor might prescribe medication for would be managed quite differently by a chiropractor. The chiropractic examination is to determine if a mechanical problem might be the cause of the patient’s complaints. A common rhetorical scenario would be:

If your hand was caught is a closed door resulting in severe pain, how would you prefer to be treated?

Prescribed the best drug available to mask the pain?

OR

Ask a chiropractor to come by and open the door?

The chiropractic mechanical examination typically involves two approaches:

Segmental Spinal Examination

The spinal column is comprised of 24 individual bones (vertebra) plus the skull and the pelvis:

7 neck bones (cervical spine)

12 mid back bones (thoracic spine)

5 low back bones (lumbar spine)

Each vertebra has multiple joints, both above and below (and with the ribs in the thoracic spinal area). Each spinal joint has an optimal ability to move and an optimal position.

The chiropractic segmental spinal examination assesses the integrity of these vertebra and joints.

Postural Spinal Examination

The overall postural alignment of the spinal column and pelvis is an important component of the chiropractic mechanical examination. This typically involves observations of the alignment of ears, jaw, head, shoulders, ribs, and pelvis.

Spinal x-rays are often used and helpful at documenting and measuring both segmental and postural mechanical problems.

Posture is important to health and physiology. Postural distortions are three-dimensional. Clinicians often simplify postural distortions by categorizing them into the coronal plane (side-to-side) and the sagittal plane (front-to-back). Evidence is accumulating that forward postural distortion in the sagittal plane is particularly deleterious, increasing pain, reducing health, and enhancing disability. This evidence is reviewed below in this paper.

There are four primary reasons for forward postural distortion in the sagittal plane:

- Forward head: This is often accompanied with increased cervical spine lordosis.

- Cervical spine kyphosis (reversal of the normal cervical spine lordotic curve).

- Hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine.

- Loss of lumbar lordosis.

Within the chiropractic profession there are a number of accepted and proven techniques to treat the segmental and postural mechanical problems that are found during the chiropractic mechanical examination. These techniques are taught at both the chiropractic university/college level as well as in post-graduate classes.

The best documented chiropractic postural technique is Chiropractic Biophysics (CBP). This CBP group has an impressive number of published works pertaining to ideal posture and methods for postural corrections. Currently the group has an excess of 200 studies in the peer-reviewed scientific literature (2).

Entire medical texts and chapters in medical texts are dedicated to posture and its influences (3, 4). An early description of the importance of good posture on physiology is described by James Oschman, PhD, in his 2000 book titled Energy Medicine, The Scientific Basis (5):

Joel E. Goldthwait and his colleagues at Harvard Medical School “developed a successful therapeutic approach to chronic disorders. The aim of his therapies was to get his patients to sit, stand, and move with their bodies in a more appropriate relationship with the vertical. After years of treating patients with chronic problems, he concluded that many of these problems arise because parts of the body become misaligned with respect to the vertical.”

“Goldthwait’s therapeutic approach corrected many difficult problems without the use of drugs. He viewed the human body from a mechanical engineering perspective, in which alignment of parts is essential to reduce wear and stress. He pleaded with physicians to recognize and correct misalignments to prevent long-term harmful effects.”

“Misalignment of any part will affect the whole system, and that restoration of verticality is a way to address a wide variety of clinical problems.”

•••••

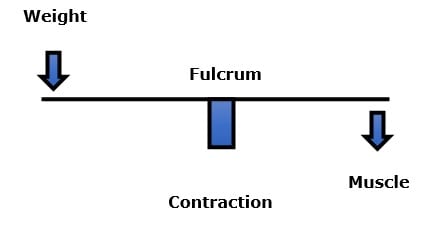

Upright posture is a first-class lever mechanical system (6, 7). An example would be a teeter-totter or seesaw. In the first-class lever mechanical system, the fulcrum is the pivot in the center. The fulcrum is where the mechanical loads are the greatest.

In upright human posture, the fulcrum is the spinal vertebra (vertebral body, intervertebral disc, facet joints). When a person has a forward postural distortion in the sagittal plane, they would literally fall onto their face if the muscles on the opposite side of the fulcrum did not contract, maintaining balance. This counterbalance contraction of the muscles is both fatiguing to the muscle and increases the compressive loads on the fulcrum tissues. The counterbalancing muscles are the posterior spinal muscles; they exist from the back of the skull and neck, all the way down the spinal column to the pelvis.

The posterior counterbalancing muscles are in a constant struggle with forward weight and gravity. Constant muscle contraction causes muscle fatigue. Weight and gravity do not fatigue. Weight and gravity eventually win the struggle. Postural distortion and its deleterious consequences tend to become worse over time unless there is an appropriate intervention.

Rene Cailliet, MD, uses an example where a patient has unbalanced forward head posture (8). Dr. Cailliet assigns the head a weight of 10 lbs. and displaces the head’s center of gravity forward by 3 inches. The required counter balancing muscle contraction on the opposite side of the fulcrum (the vertebrae) would be 30 lbs. (10 lbs. X 3 inches).

In her 2017 book Move Your DNA, biomechanist Katy Bowman describes how chronic postural distortions cause adverse tissue adaptations that become fixed and rigid unless, again, there are reversing therapeutic interventions (9). Often the beginning of these commonly found forward postural distortion in the sagittal plane are sedentary computer-based occupations and leisure activities. Perhaps the worst offending activity is the use of cellular phones (10).

•••••

In 1978, Swedish neurosurgeon Alf Breig, MD authored a book titled Adverse Mechanical Tension in the Central Nervous System (11). In this book, based upon his own surgical observations, Dr. Breig asserts that loss of cervical lordosis tethers the spinal cord creating myelomalacia and spinal cord atrophy. He states, “Patients with long-standing kyphotic deformities are at risk for progression of myelopathy with resultant permanent damage to the spinal cord.”

•••••

In 2004, physician Deborah Kado, MD and colleagues published a study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, titled (12):

Hyperkyphotic Posture Predicts Mortality in

Older Community-Dwelling Men and Women: A Prospective Study

Thoracic spine hyperkyphosis is frequently observed in older persons. The objective of this study was to determine the association between hyperkyphotic thoracic posture and the rate of mortality and cause-specific mortality in older persons. It was a prospective cohort study that included 1,353 participants.

Study participants were followed for an average of 4.2 years, with mortality and cause of death confirmed using a review of death certificates.

Persons with hyperkyphotic posture had a 44% increased rate of mortality.

“Hyperkyphotic posture was specifically associated with an increased rate of death due to atherosclerosis.” The authors note that interventions specifically targeted at improving hyperkyphotic posture could result in reduced mortality rates.

•••••

In 2005, physician Steven Glassman, MD, and colleagues, published a study in the journal Spine titled (13):

The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity

These authors measured the pain, systemic health, and disability status of 298 individuals and compared them to a full-spine lateral radiographic measurement of sagittal postural balance. A plum line was dropped from the body of the C7 vertebrae and measured with respects to the articulating surface of L5 with the sacral base. This measurement was specifically used to quantify forward postural distortion in the sagittal plane.

All measures of health status showed significantly poorer scores as C7 plumb line deviation increased in the forward direction (anterior to the sacral base). The authors note:

“Patients with relative kyphosis in the lumbar region had significantly more disability than patients with normal or lordotic lumbar sagittal measures.”

“This study shows that although even mildly positive sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, severity of symptoms increases in a linear fashion with progressive sagittal imbalance.”

“The results also show that kyphosis is very poorly tolerated in the lumbar spine.”

“There was clear evidence of increased pain and decreased function as the magnitude of positive [forward] sagittal balance increased.”

“All measures of health status showed significantly poorer scores as C7 plumb line deviation increased [forward].”

“This study shows that although even mildly positive [forward] sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, severity of symptoms increase in a linear fashion with progressive [forward] sagittal imbalance.”

•••••

In May 2009, Dr. Deborah Kado and colleagues published a follow-up study on thoracic kyphosis and mortality rates. This article appeared in the Annals of Internal Medicine, and is titled (14):

Hyperkyphosis Predicts Mortality Independent

of Vertebral Osteoporosis in Older Women

This study was a prospective cohort study involving 610 women, aged 67 to 93 years. Their thoracic kyphosis was measured, and mortality was assessed an average of 13.5 years later. The authors concluded that each standard deviation increase in kyphosis carried a 14% increased risk for death. The authors note:

In older women “increased kyphosis predicts increased risk for all-cause mortality independent of the extent and severity of the underlying spinal osteoporosis.”

“Other large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that kyphotic posture may be associated with worse health, including impaired pulmonary function, poor physical function, inferior quality of life, injurious falls, fractures, and death.”

“We postulate that the phenotype of hyperkyphosis is an easily assessable clinical marker of accelerated physiologic aging or frailty.”

“These results add to a growing literature that suggests that hyperkyphosis is a clinically important finding.”

“Because it is readily observed and is associated with ill health in older persons, hyperkyphosis should be recognized as a geriatric syndrome—a ‘multifactorial health condition that occurs when the accumulated effect of impairments in multiple systems renders a person vulnerable to situational challenges.’”

•••••

In November 2009, researchers from the Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation Medicine, Fukui University, Japan, published a study in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, titled (15):

Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy Associated

with Kyphosis or Sagittal Sigmoid Alignment

These authors assessed the records of 476 patients to determine the effects of kyphotic forward sagittal alignment of the cervical spine in terms of neurological morbidity, and specifically on the development of cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

These authors concluded that cervical spine forward sagittal kyphotic deformity plays an important role in neurological dysfunction. This was especially true when the kyphotic deformity exceeded 10 degrees. They state:

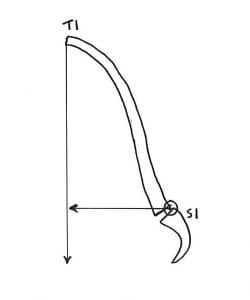

“Loss of lordosis or kyphotic alignment of the cervical spine and spinal cord may contribute to the development of myelopathy, and in patients with cervical kyphotic deformity, the spinal cord could be compressed by tethering over the apical vertebra or intervertebral disc.”

“We conclude that the [cervical spine] sagittal kyphotic deformity related to flexion mechanical stress may be a significant factor in the development of cervical spondylotic myelopathy.”

•••••

In April 2013, another article was published in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, titled (16):

Relationship Between Degree of Focal Kyphosis Correction

and Neurological Outcomes for Patients

Undergoing Cervical Deformity Correction Surgery

These authors performed a retrospective review of 36 patients with myelopathic symptoms who underwent cervical deformity correction surgery. They note:

“The normal lordotic curvature of the cervical spine is critical to maintaining sagittal alignment and spinal balance.”

“It is believed that the neurological symptoms seen in cervical kyphosis are a result of deformity-induced anatomical changes that apply pressure to the spinal cord and nerve roots.”

“The reversal of normal cervical curvature, as seen in kyphosis, can occur through a variety of mechanisms and can lead to mechanical pain, neurological dysfunction, and functional disabilities.”

“Kyphosis of the cervical spine can be a debilitating condition that leads to significant neurological dysfunction.”

•••••

In July 2013, a study was published in The Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences, and titled (17):

Spinal Posture in the Sagittal Plane Is Associated

with Future Dependence in Activities of Daily Living

These authors noninvasively measured spinal postures in a community-based prospective cohort of older adults (804 participants: 338 men, 466 women, age range 65–94 years) to determine if any such postures were associated with the need for future assistance in Activities of Daily Living (ADL). They found that lumbar kyphosis pitched the body and head forward, and this postural distortion was significantly associated with the need for future assistance in the person’s activity of daily living. These authors state:

“Accumulated evidence shows how important spinal posture is for aged populations in maintaining independence in everyday life.”

“Spinal posture changes with age, but accumulated evidence shows that continued good spinal posture is important in allowing the aged to maintain independent lives.”

“The gravity line moves further anterior as inclination of the trunk increases.” “Even mildly positive sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, the decline in health status increases in a linear fashion with progressive sagittal imbalance.”

Spinal “inclination is associated with future dependence in ADL among older adults and warrants wider attention.”

The “results indicate that attention needs to be paid to inclination in spinal posture to identify elderly people at high risk of becoming dependent in ADL.”

•••••

In 2019, a study was published in the Asian Spine Journal, and titled (18):

Hypertension Is Related to Positive Global Sagittal Alignment:

A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between hypertension and spinal-pelvic sagittal alignment in middle-aged and elderly individuals. The study used 655 participants (262 men and 393 women; mean age, 72.9 years; range, 50–92 years). Whole spine and pelvic x-rays were taken, and thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, pelvic tilt, sacral slope, pelvic incidence, and sagittal vertical axis (SVA) were measured. Analysis was done using image-analysis software.

Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg, and participants who regularly took antihypertensive medication were also considered to be hypertensive.

Postural changes start in the 30s in women and the 50s in men. By middle-age, spinal postural deformities contribute to poor health-related quality of life (QOL). The authors specifically note that when “global sagittal alignment shifts forward, it causes deterioration of the health-related QOL.”

The authors develop this model of systemic wellness, forward posture and disc degeneration:

Insulin resistance is the most important

health problem in developed countries

Insulin resistance is the precursor to diabetes,

obesity, and arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis is the precursor to hypertension

Hypertension impairs muscle circulation

Impaired muscle circulation causes muscle fatigue

Muscle fatigue causes a forward shift

in sagittal spinal alignment

A forward shift in sagittal spinal alignment

accelerates disc degeneration

The authors note that forward global spinal sagittal alignment is associated with poor health-related quality of life. They make these specific comments:

“We found that hypertension was significantly related to a forward shift in the global sagittal alignment in middle-aged and elderly individuals.”

“This study showed that hypertension was associated with forward-shifted global sagittal alignment.”

This study supports that “postural anomalies occur before disc degeneration in people with hypertension.”

•••••

Chiropractors have always understood the adverseness of postural distortions and especially a forward shift in sagittal spinal alignment. A number of chiropractic techniques are primarily concerned with assessing, preventing, and changing these and other postural distortions. The chiropractic interventions used often involve combinations of certain spinal adjustments (specific manipulations), ergonomic advice, spinal exercises, and extension (mirror image reversal) traction.

References

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- www.idealspine.com

- Kendall HO, Kendall FP, Boynton DA; Posture and Pain, Williams and Wilkins, 1985.

- Mennell JM; “The Forward Head Syndrome” in The Musculoskeletal System, Differential Diagnosis from Symptoms and Physical Signs; Aspen; 1992.

- Oschman J; Energy Medicine, The Scientific Basis; Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

- Cailliet R; Low Back Pain Syndrome; 4th edition; FA Davis Company; 1981.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second Edition; Lippincott; 1990.

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; F A Davis Company; 1996.

- Bowman K; Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement; 2017.

- Hansraj KK; Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head; Neuro and Spine Surgery, Surgical Technology International; November 2014; Vol. 25; pp. 277-279.

- Breig A; Adverse Mechanical Tension in the Central Nervous System; Almqvist and Wiksell; 1978.

- Kado DM, Huang MH, Karlamangla AS, MD, PhD, Elizabeth Barrett-Connor E, Greendale GA; Hyperkyphotic Posture Predicts Mortality in Older Community-Dwelling Men and Women: A Prospective Study; Journal of the American Geriatrics Society; October 2004; Vol. 52; No. 10; pp. 1662-1667.

- Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F; The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity; Spine; Vol. 30; No. 18; September 15, 2005; pp. 2024-2029.

- Kado DM, Lui LY, Ensrud KE, MD; Fink HA, MD, MPH; Karlamangla AS, Cummings SR; Hyperkyphosis Predicts Mortality Independent of Vertebral

Osteoporosis in Older Women; Annals of Internal Medicine; May 19, 2009; Vol. 150; No. 10; W-121; pp. 681-687. - Uchida K, Nakajima H, Sato, Yayama T, Mwaka ES, Kobayashi S, Baba H; Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy Associated with Kyphosis or Sagittal Sigmoid Alignment: Outcome after Anterior or Posterior Decompression; Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine; November 2009; Vol. 11; pp. 521-528.

- Grosso M, Hwang R, Mroz T, Benzel E, Steinmetz, M MD; Relationship between degree of focal kyphosis correction and neurological outcomes for patients undergoing cervical deformity correction surgery; Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine; June 2013; Vol. 18; No. 6; pp. 537-544.

- Kamitani K, Michikawa T, Iwasawa S, Eto N, Tanaka T, Takebayashi T, Nishiwaki T; Spinal Posture in the Sagittal Plane Is Associated With Future Dependence in Activities of Daily Living: A Community-Based Cohort Study of Older Adults in Japan; The Journals of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences; July 2013; Vol. 68; No. 7; pp. 869-875.

- Arima H, Togawa D, Hasegawa T, Yamato YGo Yoshida G, Kobayashi S, Yasuda T, Banno T, Oe S, Mihara Y, Ushirozako H, Hoshino H, Matsuyama Y; Hypertension Is Related to Positive Global Sagittal Alignment: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study; Asian Spine Journal; July 9, 2019; [epub].

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”